- The Future Is LA

- Posts

- Breaking the law, breaking our bones

Breaking the law, breaking our bones

Two streets show how far the city will go to avoid keeping us safe.

In the late afternoon of December 13th, just after the sun set over the Arts District, safe streets advocate Allen Natian was riding his electric scooter on his way to volunteer at the Streets For All holiday party. The pavement in the new bike lane on Mateo St. was pleasingly smooth, a nice change after some bumpy sections in Skid Row. But just a few hundred yards from his destination, going slowly because his scooter’s battery was low, Allen suddenly hit a large pothole that he didn’t notice in the dusky light. He fell off the scooter, tried in vain to brace his fall with his arm, and faceplanted on the pavement.

Allen is now recovering from fractures in his wrist, forearm and shoulder. His front two teeth are so badly cracked that they probably can’t be saved. (Yes, he was wearing a helmet.) He told me he will likely have to pay out of pocket for dental implants. He is currently job hunting, and he worries that his injuries will affect his prospects. Friends of Allen’s have set up a Gofundme to help him cover his expenses. He is in touch with a lawyer who may take his case.

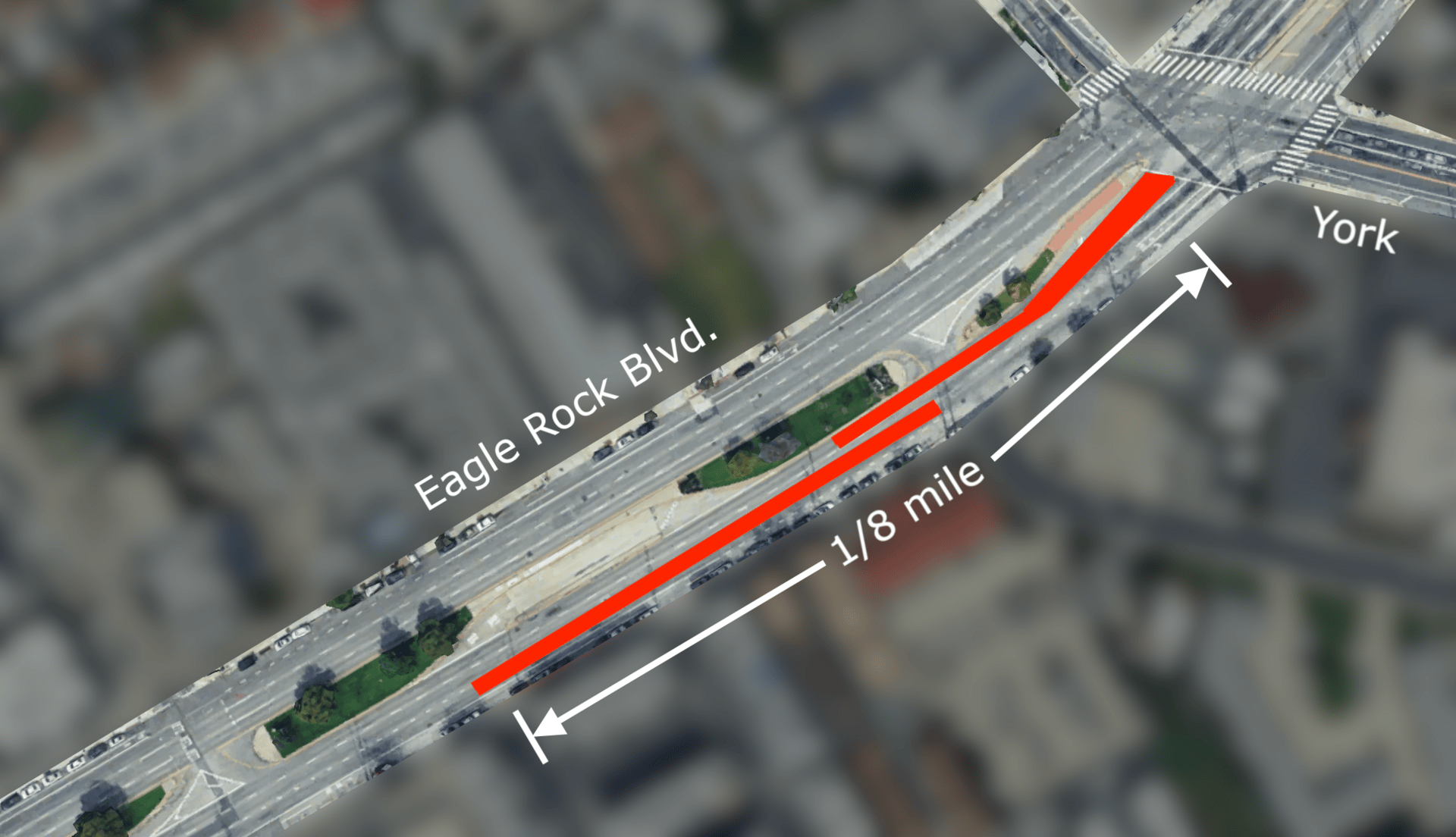

Take a look at this photo Allen took of the pothole. Notice anything?

The pothole in the bike lane on Mateo St. where Allen Natian crashed. Photo courtesy of Allen.

That’s new asphalt. It was laid about two years ago when the city built a proper sidewalk on Mateo. The bike lane was installed a few months later. But look at the middle of the street. The city didn’t repave the middle, only the sides where they fixed the sidewalk. Allen’s pothole is in a “large asphalt repair,” the partial repaving that is the only kind the city is doing these days.

Today, Streets For All founder Michael Schneider and I published an op-ed in the LA Times laying out why the city stopped fully repaving streets and started doing these large asphalt repairs. Mostly it’s about money. When a street is fully repaved, the city is required to put in updated curb ramps, and that makes repaving more expensive. What’s more, since the voters passed Measure HLA last year, the city is required to install bike or bus lanes whenever a street on the Mobility Plan is repaved. The city’s reaction to all this? Stop repaving. Instead, only do patches and call them “large asphalt repairs.”

What our piece didn’t mention, and what Mateo St. illustrates, is that large asphalt repair is sometimes barely a repair at all. Here is what the street looked like shortly after the city finished the new sidewalk and “repaired” the street by repaving only the strip closest to the sidewalk:

That small patch in the middle of the strip of new asphalt (which is also a patch) is what became Allen’s pothole. Notice the cracks by the concrete gutter on either side of the smaller patch. I don’t know why the street got paved this way, with a patch inside a patch. But I do know that within a year or so, this brand new asphalt became a dangerous pothole. It’s not a stretch to think that if the city had repaved the entire street instead of pinching pennies by only patching it, the pothole would never have materialized, and Allen Natian would still have his two front teeth.

This is the human cost of the city’s refusal to do what it’s supposed to do to keep us safe. It’s a double-whammy. By doing only large asphalt repairs, Los Angeles is endangering us by shirking its legal duty to install the street infrastructure - the curb ramps, the bike and bus lanes - that helps us stay safe. And this tactic is further endangering us by leaving the street in a deteriorating and dangerous condition.

The irony is thick in the case of Mateo St. Here the city actually tried in good faith to put in the safer infrastructure that Allen has passionately advocated for, but the crew left the street in such bad condition that the bike lane became a trap. On his way to celebrate his and his fellow volunteers’ successes in making our streets safer, Allen fell victim to the city’s failure to do the same.

Large asphalt shenanigans

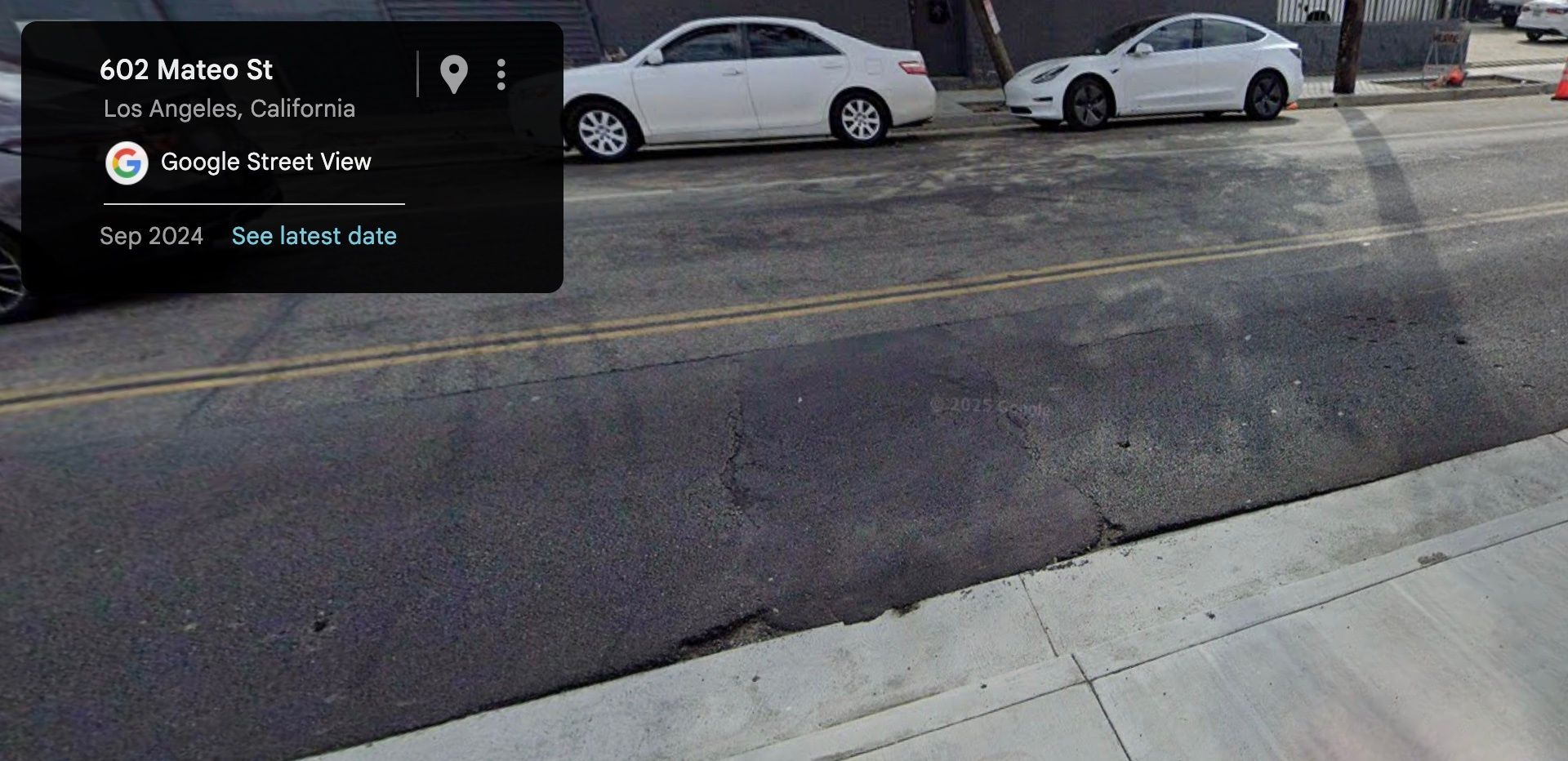

If Mateo St. shows how badly the city can bungle fixing a street, Eagle Rock Blvd. shows how carefully and calculatingly it can avoid fixing one. In October, the city got to work on a stretch of Eagle Rock west of York Blvd. that hadn’t been repaved since 2000. Instead of repaving the entire street, the city laid down a series of six large asphalt repairs. Here’s what one spot looks like:

Two large asphalt repairs on Eagle Rock Blvd. just west of York Blvd.

These two staggered patches are each about a block long, and they overlap by 75 feet or so. Instead of connecting them, the city left that narrow strip in the middle untouched. Why would they do it that way? Well, it just so happens that if the patches were connected, they would total just over 1/8 mile long, which is the shortest length of repaving that triggers Measure HLA. The Mobility Plan says Eagle Rock Blvd. gets protected bike lanes, which the city would be legally obligated to install here. Instead of doing that and making the street safer for people on bikes, we got these disconnected patches. StreetsLA even listed the two patches as separate projects on their website just to make sure nobody got the totally wrong impression that they were repaving more than 1/8 mile all at once.

The little gap between the red lines is the city’s get-out-of-HLA-free card.

The eastern end of the staggered patches at York Blvd. tells another story - how the city is using large asphalt repairs to avoid its ADA obligations. The patch goes right up to the stop line at the intersection but no further:

Large asphalt repair on Eagle Rock Blvd. at York Blvd.

Why not repave the intersection? Because that’s where the crosswalks are. The area where pedestrians cross here, just past the stop line, is known as an unmarked crosswalk - legally the same as a crosswalk with stripes. The federal government says you have to update a crosswalk’s curb ramps if you repave the crosswalk - even if you don’t repave the whole width of the street.

Regardless of whether there is curb-to-curb resurfacing of the street or roadway in general, resurfacing of a crosswalk also requires the provision of curb ramps at that crosswalk.

The curb ramps here need updating. Notice the lack of yellow bumpy rectangle:

Outdated curb ramp at Eagle Rock & York

If the patch extended a few feet farther into the intersection, the city would have to replace this curb ramp, which would add tens of thousands of dollars to the project. Heck, if the city was serious about pedestrian safety, they would stripe the missing crosswalk across Eagle Rock while they were at it. Instead of doing any of that, we got an intersection with asphalt that is still 25 years old and a crosswalk that is barely a figment of the imagination.

If you’re wondering if it’s customary for the city to pave only up to the stop line, it is not. If you look closely at the curb ramp photo above, you can see a faint line to the left of the crosswalk that marks where the city stopped when the they repaved York Blvd. in 2020. Here’s a better look from Google Street View shortly after the city finished its work:

And look just one block west - even today, the city knows how to repave a crosswalk. The catch is that this was a spot where the curb ramps didn’t need updating.

Mid-block crosswalk at Eagle Rock & Ave. 41 that got partially repaved. The curb ramps were updated in 2017 and 2020.

The federal government specifically calls out these crosswalk shenanigans:

Public entities should not structure the scope of work to avoid ADA obligations to provide curb ramps when resurfacing a roadway. For example, resurfacing only between crosswalks may be regarded as an attempt to circumvent a public entity’s obligation under the ADA, and potentially could result in legal challenges.

Potentially could result in legal challenges…just like Allen Natian’s pothole on Mateo St., or the patches on Eagle Rock staggered to avoid Measure HLA. What is the city thinking? These half-baked solutions are going to end up costing taxpayers millions in legal settlements, and those settlements will probably force the city to put in the infrastructure they tried to avoid installing anyway. In the meantime, our streets and sidewalks are getting more dangerous every day. The city might be saving money by not fixing them, but we are paying with our bones and teeth.

Well, at least they fixed one lane!

Reply